Nadine and I walked together leading the horses, father on Hook and mother on Sinker. Jemin walked next to Hook, unobtrusively ready to catch our father if he fell as we picked our way up and down hills. Our brothers walked ahead with Quill and a few of the men, the rest were behind, or scouting. We’d spent so much time sneaking through the woods in these past days that I wasn’t sure I could be loud if I tried.

Nadine leaned close to me, “Ayglos said that you were able to rescue the girls from the circus who were taken when we were, I am glad.” She kept her voice low enough that I doubted even our parents could hear us.

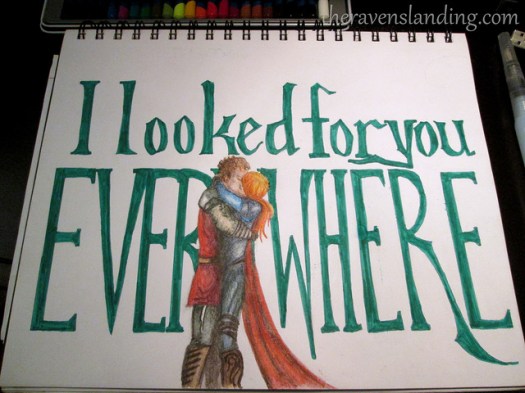

I nodded. “Jemin and I found them and got them out—I was looking for you, too, but you weren’t there.”

Nadine grimaced. “No, the officer who found us knew father and mother on sight, and guessed about me well enough. He took us straight to the Regent of Gillenwater.”

“Regent?” I asked. “Not the queen?”

“The queen!” scoffed my sister, “Don’t you remember? Queen Glykeria is only twelve, and I got the impression she spends most of her time at Hirhel. Prisoner or protégé, who can tell? We wouldn’t even have learned where she was had father not demanded to see her. No, Gillenwater is ruled by the Regent, a weasel of a man named Fotios.”

I glance at Nadine, her voice carried a bite I wasn’t used to hearing.

She continued, “He immediately packed us into a carriage and set us on the road to Hirhel. I believe he sent ravens ahead of us, so when we do not arrive we will be missed.”

“We figured they would have,” I agreed.

“I have never been more grateful for the steep slopes of the Magron Mountains,” said Nadine, “They prevented us from going straight to Hirhel, but sent us the long way to take the Bandui. We were plagued with wagon trouble, which meant little to us except that the guards were ill tempered and some were rough with us before their commanding officers could intervene. The officers were determined to bring us to the Nether Queen in tact, for her to have the full privilege of taking us apart, I guess.”

“But it made all the difference. We were able to catch up,” I pointed out, looking at my sister and trying to fathom just how close we’d come to missing them. The mercy of Eloi manifest in a few bad wheels.

We walked in silence for a time until Ayglos came back to walk with us. He addressed our father, who was looking pale under his copper tipped beard. “Quill has suggested a hiding spot outside the city walls: This side of the river is lined with villas and summer homes. Some of these have been abandoned since the conquest. They are much closer to us than the city walls, and we could rest there until he can get us a secret audience with the king.” Ayglos eyed the king with concern. “With your permission, father, he would take us there rather than make you travel further in your condition.”

Zam the Great nodded. “That sounds wise,” he replied, further confirming to his worried offspring that he was in dire condition.

Ayglos bowed slightly, nodded to Nadine and I, and returned to the front of the column to bring word to Quill and Namal. After another hour’s walking, Vaudrin and the few other men at the front came trotting past us and on back down the line. Then, to my surprise, the whole column split off and headed to the left, leaving us with only Quill and Jemin. Ahead of us the forest ended at a low rock wall. Beyond the wall spread a well-groomed lawn and flower gardens.

Quill turned right and led the way alongside the kept estates—keeping well under the cover of the trees. We passed so many hedges, orderly rows of Cypress trees, and walled gardens that I had no idea where one holding ended and another began. Occasionally there was a flock of sheep or goats and once or twice I saw the peak of a house in the distance.

The sun was just starting to sink when we came to some fields where the grass was overgrown and the cypress trees had gotten woolly without a gardener’s love. Here, the rock wall, which had run largely unbroken along the edge of the forest, had been knocked down and scattered. Quill led us over the rubble and through the overgrown meadow. Another overgrown meadow awaited on the other side of the wild cypress, and yet another beyond that. These meadows weren’t just lawns gone wild, but fields left fallow that now grew a varied assortment of grains and weeds. I noticed a lane running along the edge of the meadows to the left, but Quill led us diagonally across the lumpy, overgrown land as if he knew exactly where he was going.

Quill’s shortcut finally led us out onto another lane which in turn came to a tall but crumbling rock wall. The wall was shrouded by gangly climbing roses which were clearly enjoying their freedom. I was admiring their late fall blooms when the wall ended and Quill turned right abruptly.

We followed, and before us, rising out of the weeds and bedecked with ivy like a naiad of song, was all that remained of the villa. What had clearly once been a multi-story structure was now a burned out shell. The limestone facing for the first floor had survived, but was battered beneath nature’s adornment. A few blackened wood beams stuck out against the sky like ribs on a carcass.

Quill was standing in a huge arching doorway—though the door itself was in splinters on the ground nearby. “Please,” he bowed, “come in.”