*

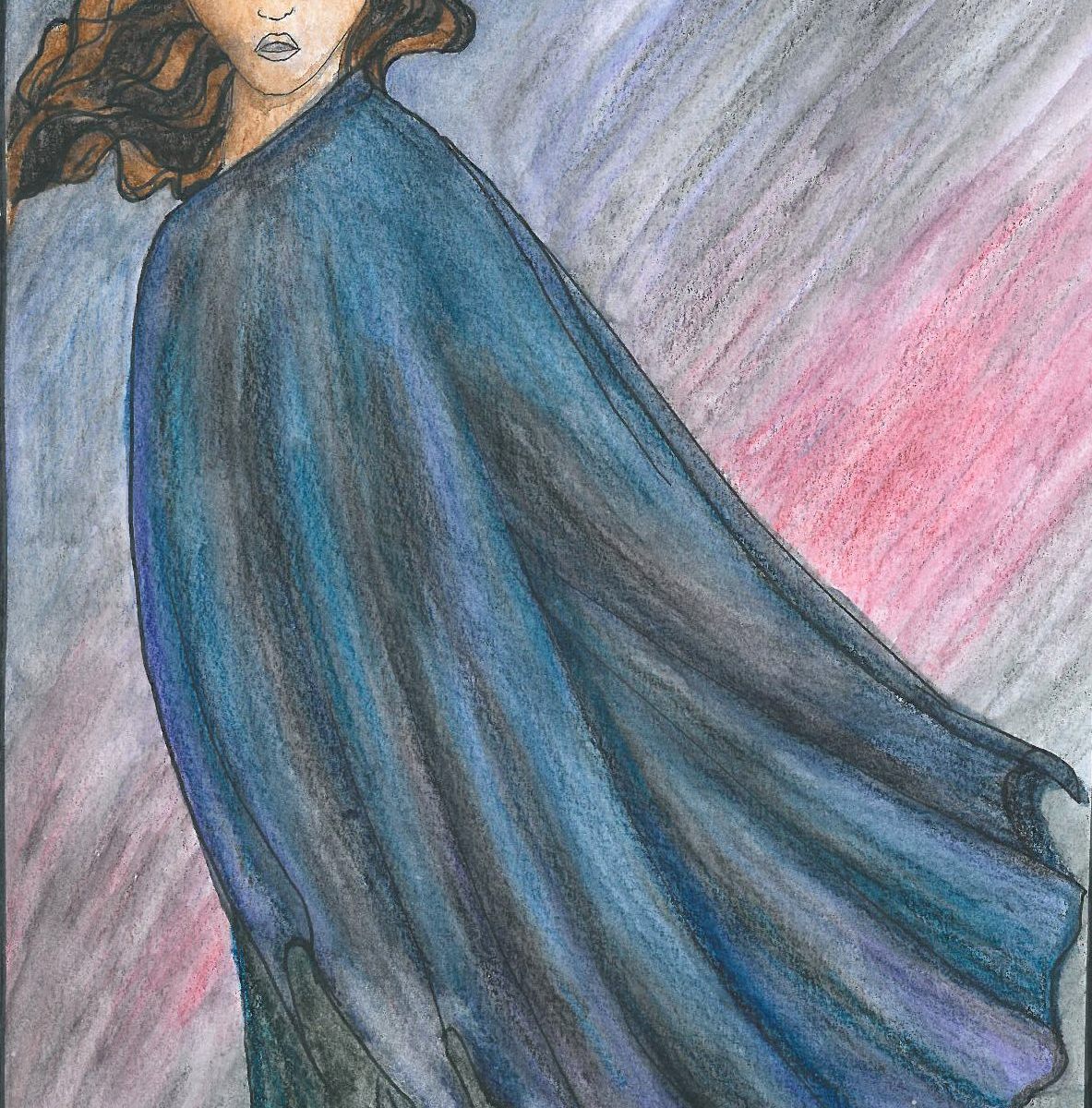

Jemin used our long walk to smear dirt on my face, muss my hair, and teach me to droop my shoulders and shuffle my feet. “Today you are not a princess, and you are not a performer. You are poor, hungry, and have never been important or the center of attention, ever. You probably spend your days bent over mending or maybe cooking,” Jemin continued seriously, “The only thing notable about you is that you’re traveling—and the only one who finds that notable is you.”

I didn’t think I stood out that badly, but I listened and emulated the walk he taught me. I hunched and thrust my neck forward and tried to imagine that I was heavy laden, beaten, and starved.

“We should let people assume that we are married,” instructed Jemin, as if discussing proper saddling. “It may offer you some protection, and is the shortest explanation for why we are traveling together.”

“Very well,” I replied, willing down a blush. This was spy work, and I was not a little girl. I couldn’t afford to be.

The people we met on the road closer in to the city didn’t even look at us, almost as if we were dirt or weeds. Or worse, starving dogs that might beg if they caught our eyes. Even at the city gates, with soldiers scrutinizing all who came and went, we were barely seen. I had thought our pilgrim gaggle was inconspicuous, but I had not known what inconspicuous was.

I tried to take in the city with an expression of shy wonder pasted on my face—as I imagined a country girl might—even though Gillenwater was not a happy sight. The harvest festival was completely ended and the carnival mood had been stripped from the city. The sun shone, but it felt terribly gray and cold inside the city walls. We crossed the little bridge over the Tryber and paused to watch workmen pick through the smoldering remains of the Queen’s forges.

“That should slow her down a touch,” muttered Jemin, before turning away. He guided us toward the market square, where we found the public well and drew water for Line and for ourselves. The glass tree was gone, though the lonely sheaves of wheat still stood here and there around the square. They looked dirty and wilted in the daylight, and without smiling people or music to make them bright.

People went about their business quickly and with their heads down. Even the normal city sounds were muted and strained.

Jemin asked someone where he could find a tavern, and we were directed a block away to a building with a covered porch and long shed row stable down the side. There were a handful of horses tethered to the hitching post out front, and Jemin added Line to the number.

I scratched the donkey behind the ears and whispered, “We can’t attract attention, Line, please be good.” He flicked his ears amiably and I followed Jemin into the dim light of the tavern.

It was midday, and the tavern had a respectable—if small—crowd of people huddled in clusters over bowls of what smelled like lamb stew. There was muted conversation all around the room, and no one really cared when we entered. I found this remarkable as I followed Jemin to the counter and tried to remember if I had ever walked into a tavern without being noticed before. Not that I’d been in a terrific number of taverns—just since the circus, really, and usually with a boisterous group of acrobats.

The middle aged man behind the counter greeted Jemin. “What can I do for you?”

“Some supper, please,” said Jemin, so meekly that I nearly didn’t recognize him. He laid a few coins on the countertop.

The tavern keeper looked at the meager coins then scooped them into his hand. “We can do with that,” he turned and scurried off through a doorway behind the counter.

While we waited, we both looked around. The few people sitting at the counter took mild notice of us. They looked like tradesmen and shopkeepers. A cobbler, I thought, and the one next to him made something out of wood—there was a fine layer of sawdust in his hair and his hands were strong and calloused. Further down, I guessed a blacksmith and probably a couple men and a woman who mostly sold things rather than made them. Our soup arrived in half-full bowls. It was not going to be a generous meal, but it was a change from the meager way fare I’d been eating.

As we ate, Jemin turned to the cobbler. “Excuse me, we’re travelers,” he said, stating the obvious, “And we saw a burned out building as we entered the city, what happened?”

The cobbler swallowed slowly and glanced at the corner before answering. We followed his look to the corner and saw a small table of soldiers, clearly off duty and immersed in their food. “That was the Queen’s forges, someone attacked it day before last.”

Jemin made a shocked face at the explanation, reminding me to look equally stunned. “Who?” asked Jemin, his voice low but carrying a touch of excitement.

The cobbler shrugged. “No one knows. You picked a bad time to be traveling through Gillenwater, I’m afraid. They are searching everywhere to find out who would dare such a thing.”

“It’s caused a powerful lot of trouble here,” put in the wood carver darkly, “We have a curfew now. And any man who is young and fit walks the streets at his own risk.”

Jemin started to act a touch nervous, “What happens to them?”

“Stopped, questioned, sometimes arrested and beaten,” replied the wood carver.

“They have no idea who they are looking for,” added the cobbler, scorn creeping into his voice, “That much is certain.” He looked for a moment as if he were going to say something else but the wood carver jabbed him with his elbow and he held his peace.

“We saw a column of cavalry on the road the other morning, was that because of this?” asked Jemin. He played innocent quite well, I thought.

The tradesmen nodded, and the cobbler replied, “They came back in a rush and bother with prisoners yesterday, so we thought they’d found the fire makers.”

“But the hunt continues,” said the wood carver.

“How odd!” Jemin exclaimed. “Who do you suppose they caught that they’d come back if it wasn’t who they were looking for?”

“Women,” the wood carver grunted in disgust and my stomach turned over.

Jemin glanced at me, “They carry off women?”

The cobbler leaned in, enjoying his possession of insight. “Women, yes. Occasionally. But rumor has it,” he cast a careful eye at the soldiers in the corner, “That they found someone really important—someone of royal blood from one of the other conquered cities—from Galhara.”