Dust and cobwebs muted the colors in the room and everything was still. So very still. “What did the queen do to Narya?” my whisper sounded loud in the quiet.

“I have no idea.”

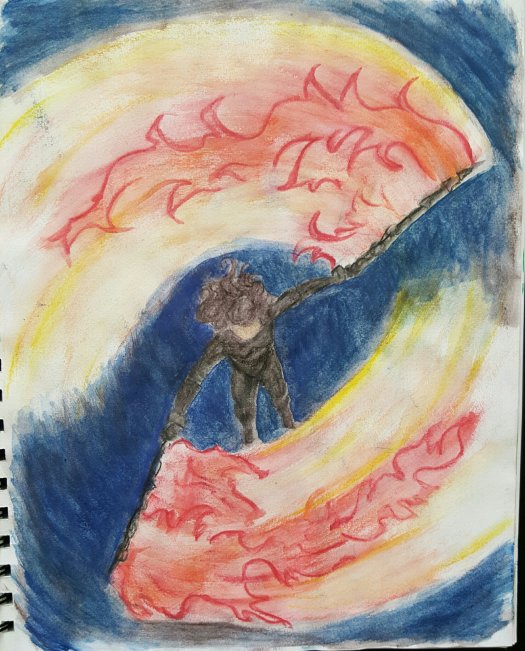

We stepped further into the room, stopping as our toes scuffed a line of ash. I picked up my skirts and stepped over the line to walk to the center of the room. The ash formed a circle on the exposed wood floor. My skin began to crawl. Dark stains crisscrossed inside the circle and led to a large stain that marred the hardwood beneath my feet. “Oh, Eloi.” I turned slowly like a boat adrift in a lake. Wicked symbols had been painted in the same dark liquid, and small mounds sat at intervals along the ash rim. I recoiled.

Still outside the circle, Quill crouched to inspect one of the mounds. “Ravens. From the colony here. They were cut in half.”

A long, sad streak led like a beacon from the central, gruesome, stain to the chamber’s main door. As if evil had entered here, and then used the blood to escape. A shudder ran through me, along with the conviction that something was here. Watching. Waiting. Hungry. I shied away from the long dry gore, stumbling in my haste.

My feet cleared the circle of ash dust, but that did nothing to calm the shivers running down my spine. I took a gasping breath, then another. My skin prickled and I backed farther away, I wanted to turn and run by was too afraid I would find something behind me. I gasped for breath again.

This was an old scene; the carcasses were so far gone there was no stench. The streak was from the body of whoever was murdered being removed.

There was nothing here.

Nothing.

At least, not anymore.

Quill stood abruptly, breaking the spell, and with a few quick steps crossing to the window. He tore down one of the curtains and tossed it over the grim tableau, wiping the ash away and pushing the carcasses together into a pile.

I left the space in a rush, as if the ash circle might reform around me of its own accord and trap me forever. I found the washroom and began hunting through the cabinets until I found a handful of towels and a large pitcher that had escaped the destruction. The running water for the tub still worked, and though it was ice cold I let it run over my hands as I filled the pitcher. Water was comforting and my breathing slowly returned to normal. Eloi. The Nether Queen did have a deal with the devil. When the pitcher was brimming, I made myself turn off the water and return to the sitting room.

Quill was on his knees, folding up the curtain around the feathered remains of the ravens. The ash thoroughly scattered.

Striding to the center, I poured the water over the blood stains, offering a prayer to Eloi as the water splashed across the symbols, obscuring them. Ignoring the stiffness in my side, I knelt and began to scrub at them with the towels. The wood yielded some blood back to the towel, but not much, as I scrubbed. Still, I began to feel better. The fear dissipated.

“We should leave.” Quill caught my eye.

I nodded, spreading the damp towels out to cover as much of the floor as possible before allowing Quill to help me up. He had the bundle of raven bodies under his arm, and I tried not to think about them as we left the way we’d come in.

We made our way, slinking through the servant’s corridors at an unhurried pace, often diverting to avoid being seen. It was a wonder to me that Quill didn’t get lost—though maybe he did, but simply got unlost again before it was an issue. By the time we returned to the King’s chambers it was getting dark and Trinh and Namal were in the sitting room eating dinner.

Namal stood when we entered, “There you are, Zare! Hesperide didn’t know where you had gone. I have been worrying.”

“I’m sorry. We didn’t go anywhere in particular.” I embraced my bother and eyed the couch, weighing if I wanted food, sleep, or a bath first. The smell of the stew reached my nostrils. Food. Definitely food first. “Where is Tarr?”

“Dinner with his ministers,” answered Trinh, setting down his bowl. “Please, join us.” Trinh was dressed in the uniform of the guard, and the dark blue cloth made his eyes seem stark as he looked between Quill and I.

Quill hesitated, but I sat down immediately and reached for a bowl. There was a pot of stew, thick with root vegetables and lamb, and a small stack of bowls and utensils. Another benefit of Hesperide’s confidence, it was easier to feed everyone. My stomach growled as I ladled the savory, steaming promise of glory into a bowl.

“Why do you have my mother’s curtains?” Trinh’s tone was sharp. I looked up to see him staring at the bundle under Quill’s arm.

The ravens.

Quill glanced at the bundle. “It seemed a fitting burial shroud for your father’s ravens.”

“What?”

I set the ladle back in the pot and settled back on the couch, cradling my bowl and refusing to shiver at the memory of the bloodstained floor. “We found some kind of evil ritual in the queen’s chambers.”

The two princes looked at me blankly, as if I’d spoken a foreign language.

“I knew your mother’s chambers had been abandoned since the fall, but had not been there myself until today,” explained Quill, “It appears that they were ransacked, and someone…” he paused, his face grim. “Someone performed some dark ritual. It was long ago—we found the remains of four ravens—and evidence that something much larger was killed there.”

Trinh’s face was ashen. Namal sat down beside me.

“Everything was all dried up and decayed,” I offered, needing the emphasis that the ritual was long done and any power would be long since dissipated.

“I gathered the ravens to give them a burial.” Quill shifted the bundle in his arms. “They bear the gold rings of Dalyn on their legs, and their deaths seem evidence enough that they were loyal to Dalyn.”

Trinh leaned forward, his eyes staring into nothingness, his jaw clenched. He was angry. Not at Quill, but at her. Abruptly, Trinh stood up. “Please excuse me, Namal,” he muttered, then strode out the main door of the chamber before any of us could move to stop him.